It was supposed to be a catharsis, a purge of years of built-up frustrations, and an exorcism of negative energy. In the end, much of the objective was achieved – though not quite in the way I’d anticipated.

Time and again, walking provides me with an antidote to the stresses and pressures that occasionally threaten to overwhelm me, to render me damn-near incapable of completing any task. When deadlines loom, emails need answering, jobs compete for attention and everything just seems too much, dropping it all to spend a few hours among the hills pays dividends.

In removing myself from a toxic environment and taking to the fells without a timetable – and perhaps more importantly without the distractions offered by a smartphone – I am able to take a metaphorical step back, to view things in better perspective. Out on the hills, soothed by a breeze and energised by a little altitude, a fresh clarity asserts itself from out of the mental maelstrom. As I view things from the perspective of a disassociation, I find myself able to prioritise those tasks which will need to be addressed immediately, identify others which might be postponed without consequence, and ignore those that can bloody well wait their turn.

On Muncaster Fell

I’d reached that point some months (well, a few years, if I’m honest) before that August day when I stepped off the train at Ravenglass, on the Cumbrian coast, into the blazing sunshine of 2022’s much-heralded second heatwave. The constant clash and demands of life and work had made this escape – a planned two-day walk between Ravenglass and Keswick, on the northern edge of Lakeland’s heart – tricky to fit in but suddenly, as the deadline loomed for the next edition of the magazine of which I was editor, I felt an urge to take a hike.

Usually, when press day’s fast-approaching, I’m on tenterhooks, stressed, tetchy, nervous to ensure the magazine is a perfect as I can make it before it’s despatched to the printer. This time things felt different: after nine years in the editor’s chair, this was to be my swansong issue, and a detachment was setting in; “demob-happy”, I think they call it. I was becoming uncharacteristically carefree, as a weight seemed to be lifting from my shoulders. I’d reached a point at which there was little more I could do to improve the magazine other than stare at it on-screen, until others provided their own input. A gap, of just a handful of days, had presented itself, an opportunity to steal a break and process the impact of the last few years. I seized it.

And so, with a laden pack on my back, camera slung over my shoulder and Pacerpoles in hand ready to stride off into the hills, I found myself alighting the train at Ravenglass. I turned left, for the footbridge over the line, only to hear the guard telling others that it couldn’t be accessed from the platform. He was mistaken, but his error led to a brief encounter with a fellow passenger who’d emerged from the carriage behind.

“John Manning?” I turned to see who was addressing me. Blow me down – Reg Davenport, a master from the grammar school I’d attended forty years ago. He’d somehow recognised me despite the beard, glasses and the legacy cask of real ale stuffed up my T-shirt. He introduced me to his wife, Mary, and we became immersed in a discussion about old times and, it transpired, a mutual love of the fells. I shared some of my apprehensions about the walk I was about to undertake – my cumbersome pack weight, a dodgy knee and a lack of fitness – and he wished me luck as we parted at the station entrance. The meeting, coupled with the day’ sunshine, was surely a good omen, and I was grateful for the distraction from my demons. On long walks I’m often my own worst company, as negative thoughts overtake and drag me down like a pack of hyenas.

I picked up the path to the crumbled remains of Ravenglass’s renowned Roman bath house and, after a trudge through the edges of the Muncaster Castle estate, began the gradual ascent of Fell Lane, the walk’s first test: long, steady and uncomfortably hot, with numerous halts to draw breath and sip from the three-litre water bladder that contributed to my onerous pack weight. Shade from trees either side of the lane was welcome but I eventually emerged on to open fellside. As the views began to open out, so the heat intensified.

The panorama from Muncaster Fell’s westerly summit on Hooker Crag (758m/231m) is superlative – it feels like a magical gateway to Lakeland, and that was just what my mind needed. East lay rocky Harter Fell and the flattened cone of Caw, to the south sat Black Combe, while to the north-east stood Lakeland royalty: Yewbarrow, Whin Rigg, Lingmell, Scafell, Bowfell and the Crinkles. I made a mental note to return with my kids, soon, in the hope that the view might work its magic on them.

Though it still seemed a long way off, it was into that mountainous country to the north-east that I was bound. The gentle, only occasionally steep and intermittently boggy descent to Eskdale Green brought me briefly alongside the Ravenglass & Eskdale Railway, past the Outward Bound Centre, over Low Holme and into Miterdale, to cross the River Mite on a small packhorse bridge. Again, trees offered shady respite from the heat as I climbed the bridleway on to Irton Fell (1,292ft/393.9m). Approaching the forest edge, I paused to chat (and catch breath) with a local walking her dog. This was her daily round, and the heat didn’t seem to bother her (though she was descending, and unencumbered by a 15kg pack) but we agreed that a cooling drop of rain would be welcome.

To Illgill Head

On the open fell, I was caught up by a fellow Yorkshireman who, like me, had started from Ravenglass, on a train that had landed almost half an hour after mine. Having booked a bed at The Wasdale Head Inn, he was unencumbered by tent, sleeping bag and stove, and was obviously fitter and moving much faster. We wished each other well, before he continued along the bridleway towards Nether Wasdale, only to re-appear several minutes later on the path I was following, over Illgill Head. If his navigational skills had been the cause of his weaving, I might yet beat him to Wasdale…

Except Wasdale wasn’t my intended halt. I planned to camp earlier, possibly at the head of Burnmoor Tarn, perhaps on Illgill Head itself, perhaps on the descent between the two. The wide ridge – a grassy expanse that seemed at odds with the rocky profiles ahead – seemed like a pier, bearing me up into the heart of the mountains. Deep, rocky clefts to my left plunged down, however, I knew, to the unconsolidated boulder fields of The Screes, that run down into the depths of Wast Water. On the lake’s glittering surface far below I could see paddleboarders, and campervans occupied almost every available spot alongside its western shore.

I half-heartedly checked out the fell’s hags and peaty pools for a suitable camp site, but it seemed too early – my shadow was still not twice my own length – and the water anyway looked stagnant for safe consumption. Rapidly improving views of Wasdale’s mountain heartland drew me on: across Wast Water sat Buckbarrow, Middle Fell and Yewbarrow, Kirk Fell, Gable, Lingmell and Scafell, while wheeling to the east revealed Slight Side, Grey Friar, Coniston Old Man and, again, Harter Fell and Caw, each no less impressive for the light veil of an early evening heat haze.

Distractions, distractions… wasn’t I meant to be putting the world to rights? Often, when I try to escape confrontation with the sources of stress by fleeing to the fells, my solitude is interrupted by the voices of my tormentors. I’m hounded by imaginary conversations in which I’m verbally bludgeoned by negativity. Somehow, though, today the stunning landscape was a complete distraction, overriding all other thoughts. I allowed myself a wry smile, momentarily amused by the thought that those whose maleficence had triggered this walk would be sweating in an office. And then the beauty of the fells drew me away once more.

I eventually pitched in Wasdale. The descent from Illgill Head’s 1,998ft (609m) summit had proved too steep and dry for a comfortable camp, and my tired legs had revolted at the thought of diverting to Burnmoor Tarn, a half-mile off my intended route. That unexpected – and uncommon – weariness had, troublingly, worsened next morning, when I rose to pack away my tent and hobbled across the campsite to refill my water bladder.

As I left the site, a cyclist turned into the lane at speed. I was sure I recognised Lindsay Buck, the “Wasdale Womble”, whose daily, unpaid efforts to keep the popular paths up Scafell Pike clear of litter have earned her the respect of the Lakeland outdoor community. I called out, but assume she didn’t hear me – she maintained her speed and disappeared in the direction of the National Trust campsite. I’d love, one day, to be able to thank her face-to-face for the good that she and fellow Womble Mick Pearce do; their positive contributions seem at odds with the actions of many.

Hobbling alongside Mosedale Beck, I took stock. My original planned route from Burnmoor Tarn had been to scale the Scafells, cross Sty Head to Great Gable, then follow trails over Brandreth and Grey Knotts to Honister Pass. From there I’d tackle steep Dale Head head-on, and cross to High Spy before coasting into Keswick over Maiden Moor and Cat Bells. It had seemed feasible on the map yesterday but now, with the weighty pack, a heatwave in full swing, increasingly wobbly knees and poor fitness levels, I re-thunk things: behind the Wasdale Head inn, I bore left towards Mosedale, for Black Sail Pass.

Mosedale

It’s a few years since I’d visited Mosedale and its wild nature, its rugged emptiness, impressed themselves afresh. Fellranger guidebook series author Mark Richards and I have, on several occasions, discussed the notion of “wild refuges”: natural areas with minimal modern human intrusion, which deserve levels of protection over and above existing designations such as National Park, Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, Site of Special Scientific Interest or National Nature Reserve. Qualifying areas would be those where the hand of Mankind has been minimal to the point of barely detectable. Such areas – the upper reaches of Eskdale always comes to mind as perhaps the finest example – should be declared inviolate, left for Nature to manage herself, and surrounding areas nurtured in a way that complements and even helps to improve the comparatively pristine state of their neighbour. The aim wouldn’t be to simply keep those core areas free of development, but to permit them to expand, by slowly removing forms of land management from surrounding areas and retreating, allowing Nature to thrive in our wake.

To my eyes, this morning, Mosedale fitted the bill. Other than the path itself and a wall or two, Mosedale – more like a high Scottish corrie than a Cumbrian Dale – seemed untouched, a peaceful retreat where Nature and a troubled spirit might heal.

A quarter of the way up the path, I paused for breath and to chat to a walker who’d already completed most of his day’s walk and was returning to the inn for breakfast. Hugh and I, it transpired, shared journalistic backgrounds though we’d each embarked on more family-oriented adventures later in life. He asked whether I knew of another local reporter he’d been acquainted with and was shocked when I told him that magazine columnist Alen McFadzean had died a few years ago.

Al – journalist, geologist, mines expert, fell-walker and gentle, kindred spirit – was one of the finest of the many talented writers I had recruited to the magazine during my stint as editor. Hugh and I shared a regret that neither of us had met him face-to-face; conversations had only been by phone or email. Al was one of the good guys… After perhaps half an hour Hugh and I went on our ways, but while we’d met as strangers I felt we had parted as friends.

Looking to Yewbarrow from Black Sail Pass

Mosedale’s quiet was shattered by a rumbling RAF Hercules flying across the valley bottom and round the back of Yewbarrow. I’m no fan of aircraft flying over National Parks but have to admit to sharing excitement at the spectacle. In turning to photograph its flight I also snapped hikers from the Netherlands, who soon caught me and became on-off companions for the remainder of the climb. They were experienced, well-equipped with maps and guides for their journey on foreign soil – far more so than a Pillar-bound party of young Cumbrians encountered, who carried little in the way of gear and were following an app with pitiful mapping. I’d set them right as they’d wandered off-route up Gatherstone Beck, but can only assume that they returned safely to Wasdale.

I eventually parted company with the Dutch couple on the pass, expecting to be swiftly overtaken but it was a while before we met again. I’d already been sat supping coffee outside Black Sail Hut for half an hour by the time they rolled up. I’d last been here six years before, in my role as magazine editor, when climber Alan Hinkes had re-opened the YHA hostel after a £325,000 refurbishment. We’d walked up from the car park below Bowness Knott, along with forty-seven kids from the local Ennerdale and Kinniside primary schools, in a deluge and arrived there feeling like drowned rats. It was in complete contrast to today’s glorious sunshine, conditions in which Black Sail becomes a hub for walkers – many on Alfred Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk – and mountain bikers.

Black Sail Hut

A tall, well-equipped American strode in as I enjoyed my brew. We shared tales of trails enjoyed. Then he caught his breath, apologised as he momentarily choked up, then confided that he and his wife had planned the walk some years earlier only to be thwarted by her cancer diagnosis. Now, he was bearing her ashes from St Bees to Robin Hood’s Bay. The demons that had driven me out on this walk were put into perspective.

As he moseyed off for Windy Gap and Seathwaite, the smell of cooking distracted me: Alex Hodgson and Tim Heald were frying up bacon on the grass outside the hut, in the hope that the scent might lure Alex’s sprocker spaniel Apollo down from Haystacks. He’d disappeared while chasing a scent, several days earlier and more than a hundred other fell-walkers had offered to join the hunt, on the ridge high above us, here in Ennerdale, and around Buttermere. While the friends’ distress was palpable, the willingness of others to help was life affirming.

My retreat from the fells followed the Coast-to-Coast route down Ennerdale. It was, if anything, longer than my intended Keswick route, the surface harder underfoot, but avoided those steep climbs over Gable and Dale Head, which my ever-wearier legs could well do without. And it held its own appeal. As well as the glorious woodland, in various conditions throughout the valley as rewilding efforts continue, going against the C2C’s flow enabled me to meet and chat with other Coast to Coasters – including two lads confident about covering its 190 miles in just six days, despite the already late hour of the day and the daunting distance remaining to their first overnight in Grasmere. Alex and Tim also overtook me on mountain bikes; I passed them again as they sat on the trackside grass, frying more rashers in the hope of tempting Apollo to reappear.

Hours afterwards, sat in The Shepherd’s Arms Hotel in Ennerdale Bridge with the afternooon’s first pint of Keswick Bitter in-hand, I slipped off my boots to give me feet some air – and that was when I discovered the cause of my tired legs.

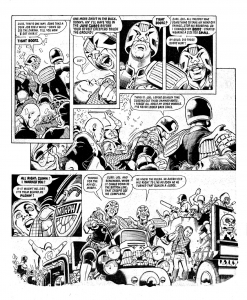

When I was somewhat younger, I was an avid reader of sci-fi comic 2000AD (“24p Earth money,” my sister used to mock). One particular story featuring the comic’s lead character, Judge Dredd has always stuck in my mind. In A Question of Judgement, the brutal future cop starts to question the accepted, brutal methods of law enforcement – essentially “shoot first, ask questions should they accidentally survive”. He tracks down his ageing mentor, Judge Morph, for advice. Should he take a break, Dredd wonders out loud, give himself time to think?

“Sure, that’s one way,” replies Morph. “Some take a desk job for a while – some go see the shrink. Tell you how I got over it. Tight boots… All I needed was something to take my mind off things, stop me brooding. So I changed my Boots – started wearing a size too small. By Grud, did those boots hurt! Thing is, Joe, I spent so much time cursing out those damned boots, I forgot all about my other worries. I’ve never looked back since.”

And that was my problem. In the rush to get out of the house and catch the train two days earlier, I’d grabbed a pair of boots from my pile of test gear and pulled them on – and they were a size too small. Perhaps wearing tight boots did take my mind of things, helped me to brooding on so many worries – but I’m sorry, Judge Morph, physically it just doesn’t do you any good whatsoever.

And yet I sensed my demons had flown, thanks not to tight boots but to the distractions of a stunning landscape and the positive encounters with everyone I’d met along the way. People. From the moment I stepped off the train to walking into the pub with two friendly Coast to Coast walkers, I’d experienced only positivity and warmth from everyone. Even those confronting personal issues had been optimistic, enthusiastically throwing their hearts into whatever they were trying to achieve. Smiling, happy people – there might be a song in that – in stark contrast to the cold, brusque, sterile relationship with a client that had spurred me to step out into the fells. Those dour, negative vibes that had long-cast a fug over my mood, had evaporated with the burning sun. The mountains, the people, had worked a special magic, not giving my troubles chance to stew and weigh me down. I’d brought home a similar lesson from my 2,653-mile Pacific Crest Trail walk in 2004 only I’d misplaced it somehow, amidst the kerfuffle of being mired in work, deadlines and the like: while the landscape is vital, the influence of good people is even more so. A positive encounter will set you up for the next challenge, inspire you to spread some of your own sunshine among those you meet.

Goal achieved, catharsis attained. My legs might have been weak, my pack heavy, but my spirit had become stronger, and my soul had been lightened.